Black Bodies, Feminism, and Representation. Is the use of the body in art the most effective way to examine social inequities and help to progress the surrounding conversation?

The body being one of if not the most sacred pieces of humanity, is also often one of the most scrutinized, abused, and controlled entities of our society. It has been used to judge, influence, and portray humanity, creating a classification system in which certain validations are required for participation. The body, and its representations, have also been used to spark debate, incite protest, and warrant further study into its meaning to science, politics, and art. The body has been used to make political statements against censorship and control and promote beauty in the human form. This duality sometimes gives way to endless debates about the body’s representation in society.

Artists have long been truth-tellers of society through the masterpieces that they create, sometimes the messages are hidden beneath the surface, and other times so direct that it has been known to resonate immediately with its viewer. A great artist or artwork is one whose message continues throughout time as a capsule of the current moment. Like the body, this capsule contains stories of the past and allows for future examination and debate.

I will examine three artists and their works that I believe help demonstrate a societal outlook on the body. Barbara Kruger, David Hammons, and Robert Mapplethorpe are all prominent in their fields of study with interesting works that deal directly with the human body. Critical, Controversial, and Timely, these artists demonstrated the use of the body as a medium, as a representation of judgment, and to fight against laws that were set to determine who was in control of its essence. The question I have is whether or not the use of the body in art is the most effective way to examine social inequities and help progress the surrounding conversation.

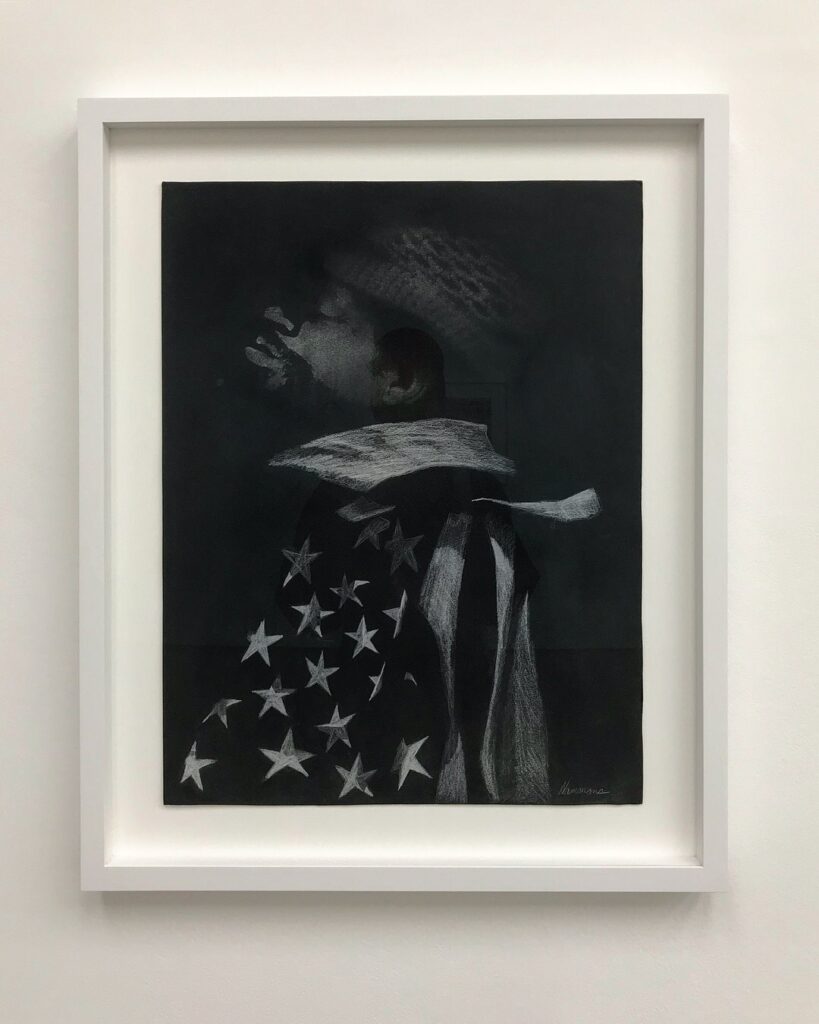

Specifically, three prominent works by these artists come to mind when I think of the representation of the body in art. David Hammons’ America the Beautiful, 1968, Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground), 1989, and Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Black Book (1986), are three works that will live forever because of the connections to the representation of the body in different forms in their current moment.

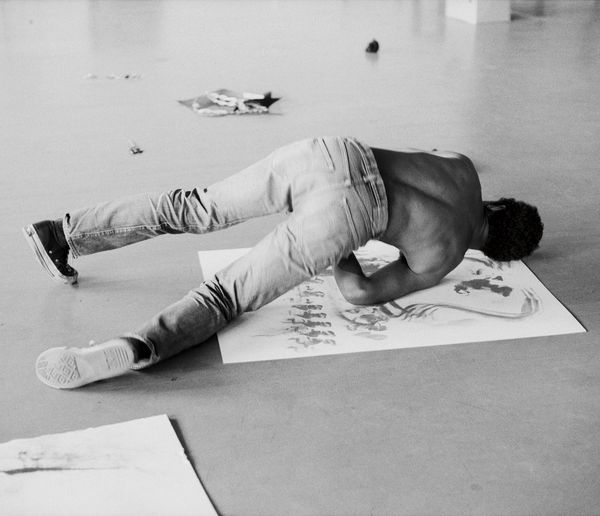

Historically, through slavery, Jim Crow laws of the American South, and the Civil War, black bodies have been an instrument in the development of America. In 1968, when the civil rights movement drew to a close, these same bodies were still seen as inferior and a target to American society by the government, media, and corporate community. Inspired by the body movements of Yves Klein’s Anthropometries and using his body as the tool for creation, Hammons created this piece by covering himself, torso, limbs, and face in oil and margarine, then pressing himself against the paper in almost a reenactment of black bodies being slammed on police cars. Showing the smashed impressions of his physical form, Hammons can evoke the impact and change on the body structure as it hits the surface revealing only certain features in the form of a manual x-ray or a thumbprint.

Hammons used this method of production in an assembly line fashion hinting at the continuous strain on the body as in fieldwork for slaves. Adding the American Flag as a key part of this piece goes to symbolize these horrors wrapped up or covered up within the American Constitution. Creating lithographs of these prints I believe hinted at the countless bodies being used in the horror with the reproductive process being used as a metaphor for American production.

In using critical race theory in this work Hammons identifies himself with the examination of society through race, law-making, and the elite class. Hammons challenges the notion of the rejection of “color-blindness” with himself as the tool insisting that the viewer recognize that his own body was the sacrifice for the creation of this work. Hammons demands society to engage with this work through the eyes of privilege and discrimination which continue the overarching hand of supremacy in America. Using this work as almost a parable for the black experience in America, Hammons attempts to preserve the history of black pain in the period by documenting its effects on the mind, body, and character of its marginalized citizens.

Hammons’s use of this patriotic symbol juxtaposed with the black body (or representation thereof) to emphasize the racial tensions in the United States during this period. Titling the series, Black First, American Second, the artist demonstrates the discrimination that Black Americans felt from their white counterparts on issues of justice and equality. The body pressed fully against the paper also gives the viewer the feeling of a fallen war hero laid in his casket at a funeral, I believe making a sympathetic gesture of black people’s contribution to the country. With the Vietnam War still at its height, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr, and the start of the Black Power Movement, America the Beautiful, 1968, and its production process acts as a dedication and sacrifice of the black body.

America the Beautiful, 1968 is a stark reminder of the Dred Scott decision of 1857 that spoke to the validity of citizenship of black people in the United States. By applying the flag as a reference Hammons brings into play the inconsistency of the American government in providing liberties to its black citizens. Using Derrick Bell’s research on critical race theory as a premise, I believe Hammons used art to communicate issues of the community that previously fell on deaf ears. By imploring these thoughts in his work, he (Hammons) invites the viewer to examine the interpretations of American history and how it’s consistently played out unfavorably in the American justice system.

I would consider this piece as a component of ethnic studies for its content and contention with the Eurocentric perspective. Ethnic studies were conceived in the civil rights era when Hammons started these works and sought to change the way the stories and representations of African Americans are viewed. Hammons, I believe, felt the best way to accomplish this reformation was to show the body and its features as an accelerated instrument of explanation.

Body Politics, referring to practices in which society tries to regulate control of the body, has been the cause of national debate on many issues, and the Black First, American Second, series speaks directly to that theory. Hammons takes ownership of his body to deliver a message that challenges governmental procedures. He uses his body to source knowledge production and extracts a conversation about how black males are viewed by the current society which allowed him to stage an artistic protest instead of a physical one.

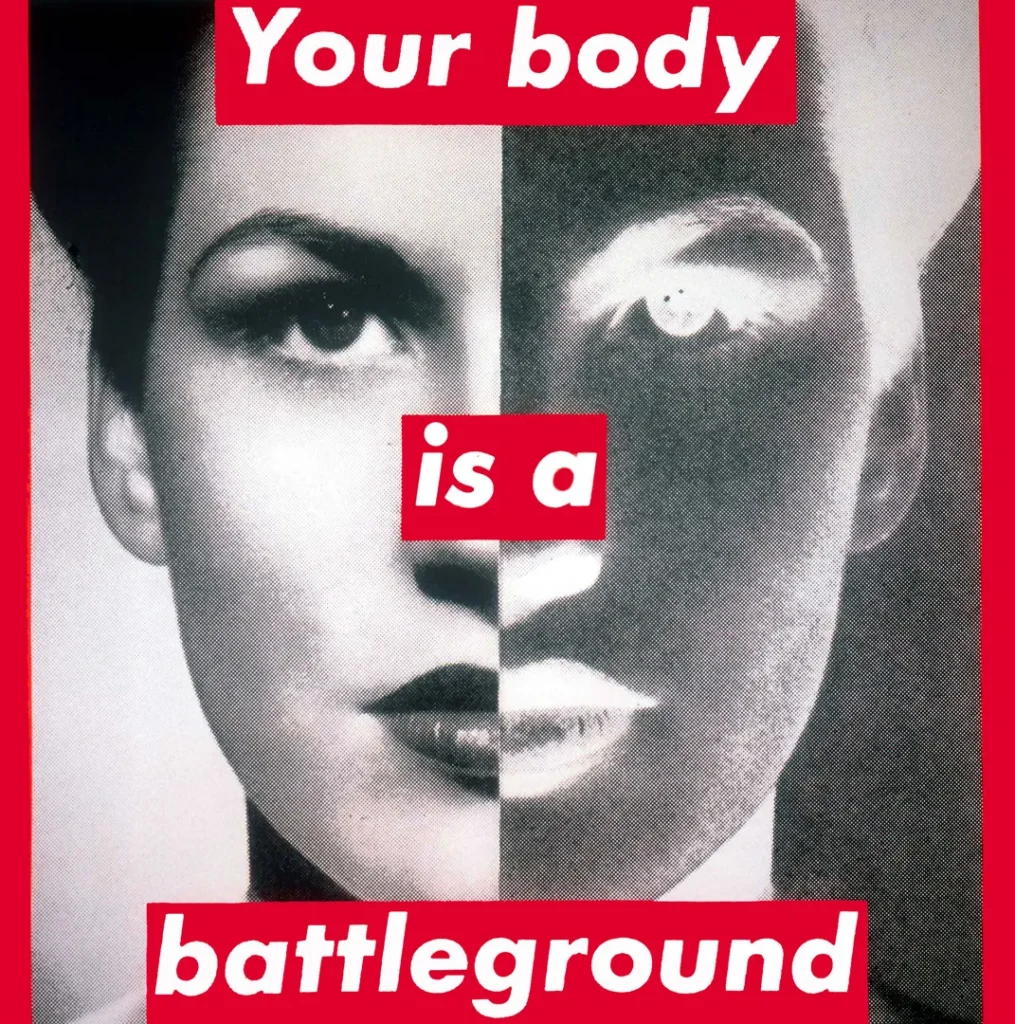

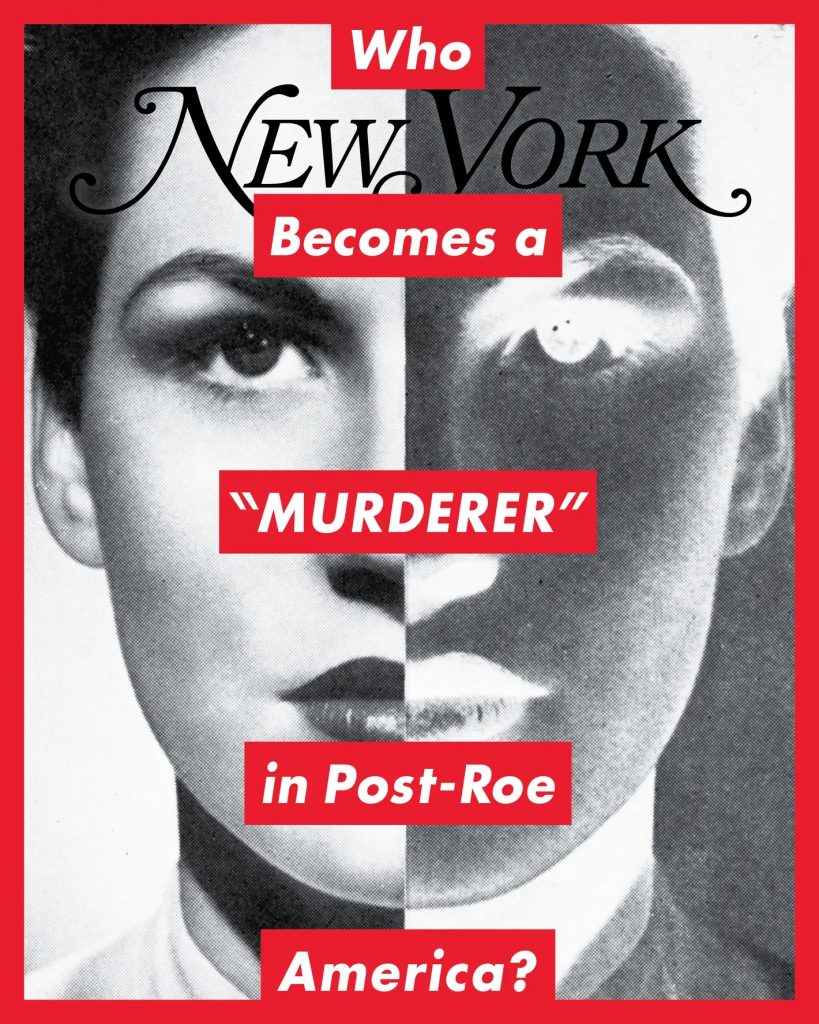

Barbara Kruger uses her work Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989 as a catalyst to the debate on women’s rights in the ’80s and was produced to coincide with the Women’s March on Washington. There was a rising number of demonstrations and protests in the ’80s because of new anti-abortion laws that were going directly against the verdict of the Roe V. Wade Supreme Court Decision of 1973. Kruger’s work aligns the protests with the theory of Body Politics and control over the human body.

This work with its large canvas and bold imagery almost yells at the viewer to take charge of their body. It presents the face of a woman divided into two with the negative split evenly down the middle almost presenting (again as referenced in Hammons’s work) an x-ray of the face. The duality seems to represent the people on both sides of the debate about women’s rights and who gets to decide.

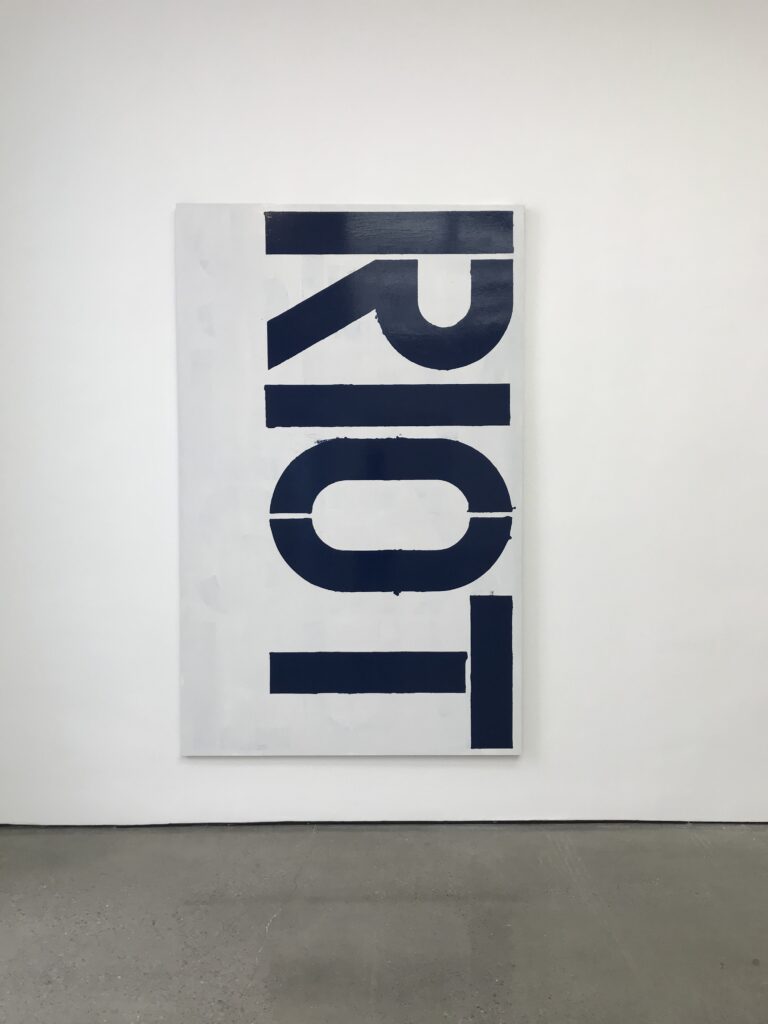

The bold words of “Your Body Is A Battleground” speak to how the war has changed from “As seen on TV” to within the female body. With the bold red and white Barbara invites the viewer to stop immediately and heed the words almost reminiscent of the war posters of the late 1940s and ’50s, when they placed bold directives such as “Join The Army!” with a strong figure to entice other potential citizens who were still undecided. By using art in the style of tabloid marketing and advertising, Kruger was able to address media politics in a voice that was familiar and effective.

In this work, the body is used as a metaphor and a representation of a movement against the law. Kruger addresses the female population with action, encouraging them to seek knowledge and awareness of the current situation that affects them all. This call to action addresses a mental as well as a physical protest enabling the change in the habits of women in society as it pertains to how they view their bodies and the rights and responsibilities in making choices. Like Hammons, the work subtly calls for a mental overhaul of the social norm with the body being the catalyst for the widespread debate.

Within the body politics structure, female bodies are seen to be vulnerable and not able to be “warrior-like” which Kruger challenges in this artwork. Adding what is seen to be a beautiful woman appropriated from a magazine, she also points to the view of women as objects in society and hints at feminist views of the male gaze. These gender politics have determined who should be vulnerable and who commands respect. The male gaze in society has been seen as a patriarchal control over the body of a woman and Kruger uses the beauty of the female face to get the male viewer’s attention to the ultimate message. The female face in this work is seen as strong, confident, and direct, much different than what the societal norms are for women who were to be seen as docile and submitting to their male counterparts. Kruger uses the knowledge of “Second Wave” body politics to encourage women to fight against the politics that governed their bodies. By stimulating the consciousness of women and enacting a “no fear” visual element, it helped to break the long silence of women as it regards their bodies.

Kruger presents a two-part view through this work inciting action from women during the period. Using strong images (strong confident females) alongside very direct and bold text with tons of emotion, Kruger hoped to provoke a new conversation about gender politics. According to feminist theory, the male and female bodies differ in the sense that women are more “natural” than men, more corporeal, and therefore see a difference in their minds. In the sense of the corporeal, Kruger and Hammons relate within society as the black body and the female body have been underappreciated for their contributions to the growth of humanity and portrayed as “soulless” and in turn use their art as a way of combating this perceived difference among the colonizing class.

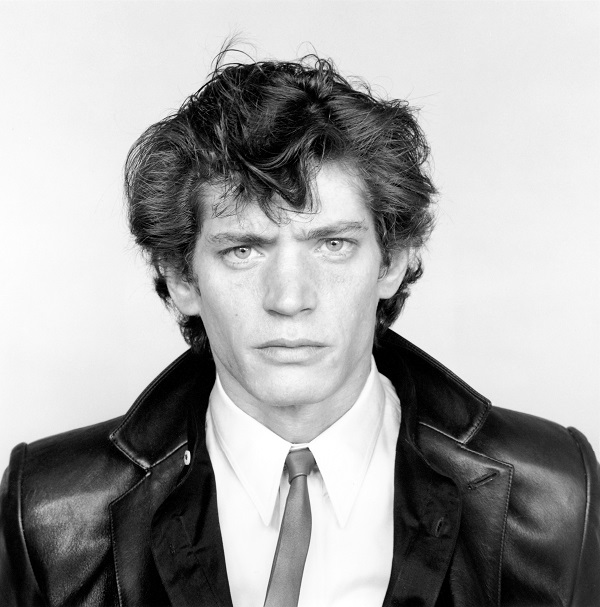

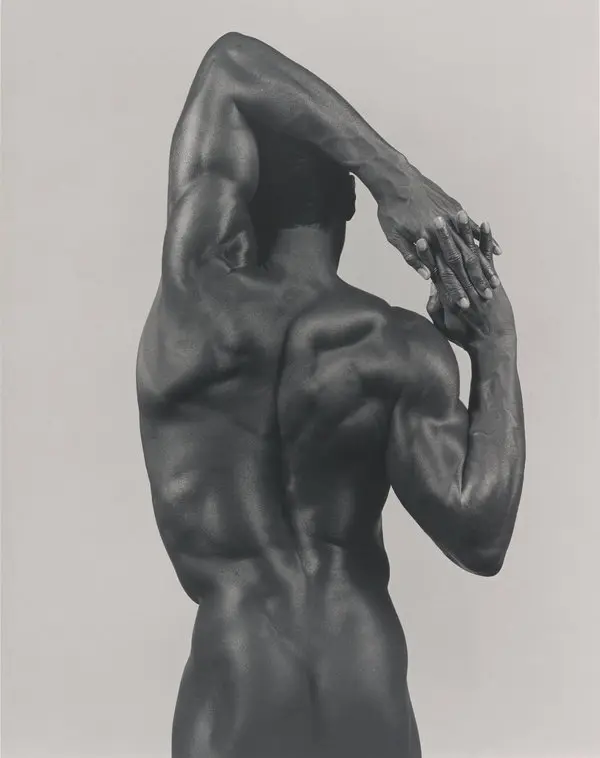

The male gaze and the presentation of the black body are also prevalent in the work of Robert Mapplethorpe which brings together the concepts of racial and gender politics of the body from the perspective of the white male in society. This gaze cites the “patriarchal power” of Mapplethorpe allowing him to assume his male role as the “looker” while the black male is relegated to the items to be perused at leisure. The Black Book, a collection of “idealized and homoerotic” nude photographs of naked black gay men, was looked upon as a very touchy project by Mapplethorpe. Embarrassed and outraged by its contents, many artists, theorists, and writers chose to put pen to paper to debate the relevance of this topic how it affected black men, and the artistic integrity of the works.

Mapplethorpe’s representations of the black men in this book set the male gaze in its eye, with Mapplethorpe being a gay man himself, also in charge of the very device used to scrutinize (the camera), he was able to portray an alternate reality of the black body to the viewer, his reality.

Historian Kobena Mercer places this gaze in the proper perspective as he infers that the photos are a “cultural artifact in the ways that white people “look” at black people and how in this way of

looking, black male sexuality is perceived as something different, excessive, Other.” In the period when these photos were taken the gay male body was being attacked and criticized, he chose to use others as a cause for examination, ultimately separating his identity from that of the subjects.

Mapplethorpe’s expose of The Black Book allowed the critics a duality of opinions about the work. On the one hand, the work completely stereotyped the black male body as a sexualized image, used only for desire or work, and on the other documented the gracefulness, power, and strength on display. Taking a queue from earlier sculptures such as Michelangelo’s marble David, Mapplethorpe tries to push forward a conversation of maleness and blackness using the consistency of the nude through art that has gone to objectify and sometimes enhance the sexuality of a subject in history.

Mapplethorpe prominently puts on display to the viewer through his “vision” that the greatest reward of the black male is his sexual prowess. Images such as Man in a Polyester Suit, which features prominently the penis of a black man and nothing else, are the only identifier of it being male or black in the photo leading the viewer to immediately look at its subject as an object. This places the black male body as an attraction giving the viewer an erotic source of pleasure without the permission of the model but with the permission of the photographer. A quote from art critic Holland Cotter describes this succinctly as “No face, no name, no person, just an anatomical fragment that translates into race = sex.”

This “ownership” of the body (or digital representation thereof) is reminiscent of the early days of the slave trade when black bodies were placed on display in public and news memos for sale. The Black Book has been said to reveal more about the pleasure-seeking of Mapplethorpe than it does to accentuate the abstract beauty of the “anonymous black men whose beautiful bodies we see depicted.”

Mapplethorpe uses this book of works also as a question of gender politics in the Western art world by substituting the nude of the white female for the braun of the black male body. With Mapplethorpe being a gay man, he looked to question a male’s role in society as dominant or overarching, and replacing that with a more harmonious visual helps to soften the public’s view on black masculinity but at the expense of being critically judged due to the nature of its content. Using the philosophy of otherness, Mapplethorpe exhibits his subjects as different from their “political philosophy” and in their “non-conformity” to social norms where the black body is seen as the antithesis of American society.

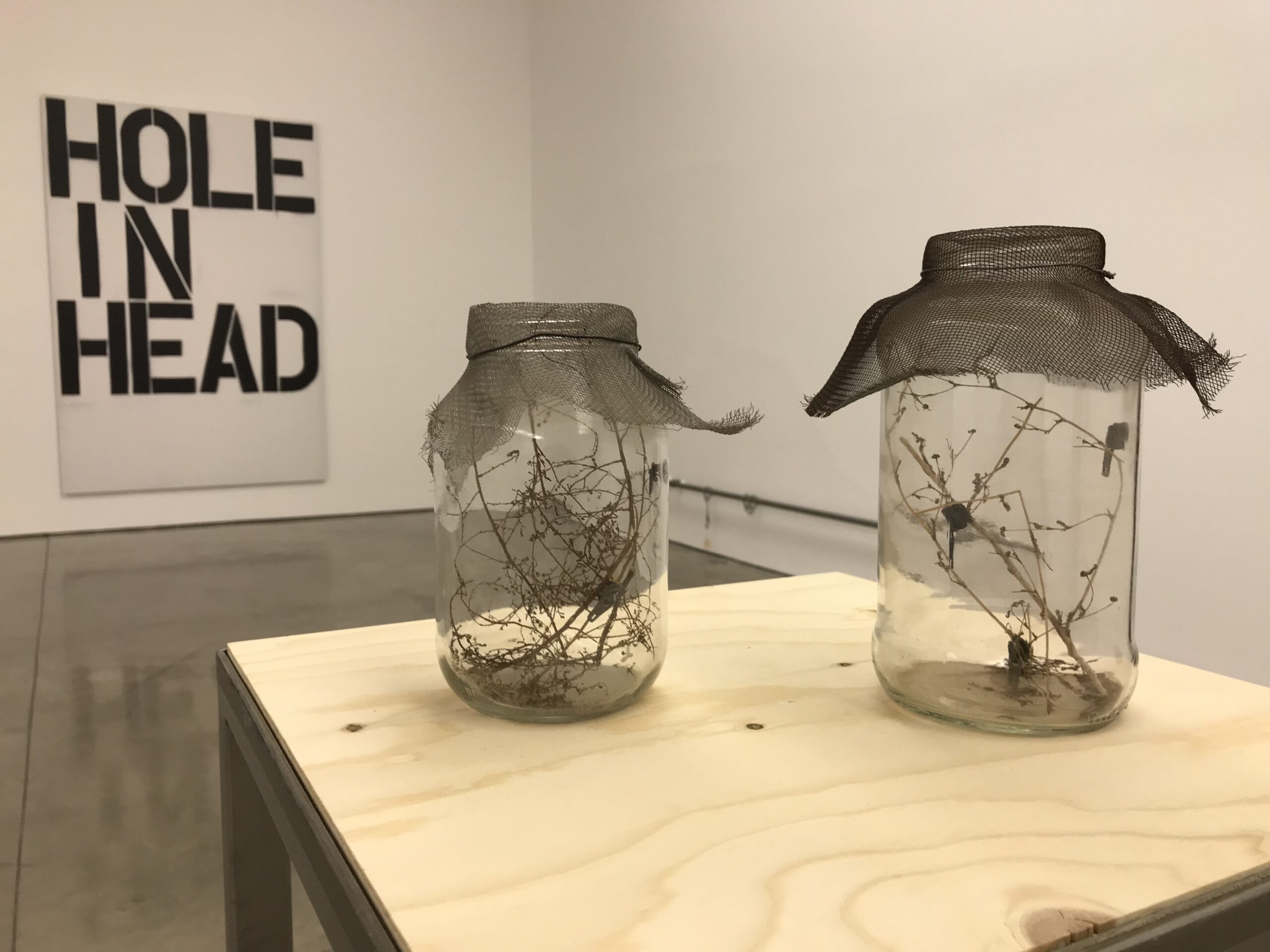

But how do these works change the way bodies are viewed in society? I believe the consistency of action and boldness in the presentation and the messages are what tie these works together. Mapplethorpe’s works and the distorted or misrepresented meaning prompted artist Glenn Ligon to create a contention or retraction titled Notes on the Margin of The Black Book, 1991-93, which sought to “sort out the effect these images of black masculinity had on him as well as on others”.

Barbara Kruger leads a revolution of text-based works that inspire street clothing brands and more and her message and design style have been the calling card to many works of protest. Hammons continues his message of black empowerment using common items to push the conversation and understanding of the black experience in America. They also touch on the key topics mentioned in this text referring to gender, race, and the theory of Otherness. These bodies, female, black, and gay were seen as abhorrent as racism itself, and through these works and practices of art, these artists were able to present new meanings, representations, and control over the body’s identity.

The importance of these works lies in their place and time in history and the context in which they were created. Rooting themselves in protest, activist, and resistance style practices, these works sought to change the perception of the black, female, and gay bodies and by using the body as the main component of the political study, these works helped to inspire their peers and all affected by their respective struggles. Hammons aspired to show the strain, strength, and resilience of the black body and its relation to the ongoing civil rights struggles in 1968, Barbara Kruger aimed to take back ownership of the female body and oppose laws set in place to control choice at the Women’s March in 1989 and Mapplethorpe’s work caused an uproar on both sides leading to a demonstration in which his photos were displayed on the building in protest. These body politics helped to dismantle the oppressive laws and impact of the ruling class on those bodies they deemed “inferior” by expelling the essence contained within.

The body remains a hot topic in art with some of these same topics at the forefront. From Marina Abramovic’s Rhythm 0, 1974 to Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, 2016, the use and presentation of the body and its status in society are constantly being challenged. These challenges are always a catalyst for global change and improvement without the physical war and loss that usually come with it. The body is the most consistent thing across humanity and I believe it is the easiest topic to engage humanity and allow them to look into themselves for the correct answer. These artists are prime examples of protesting, activating, and demonstrating while still attempting to educate their audience on issues and their practice will continue to influence artists to follow in their footsteps. These conversations through art justify the practice as a contributing factor to the development and its importance as a voice for the sometimes voiceless.