The TEN Series: J. Michael Walker

There aren’t too many artists in the City of Los Angeles that offer soothing remedies when visiting their studios. Most of the studios I’ve visited during my time immediately adopt the mind state of the artist – organized chaos. Visiting the creative space of Los Angeles-based artist J. Michael Walker (known affectionately as “J. Michael”) has a different feel, and now I understand why. Born in the American South (Little Rock, Ark), Walker has a soft audible charm allowing you to feel comfortable in his presence. His hair tied back and buttoned-up shirt with rolled-up sleeves is usually how you’ll find him, comfortable but ready to contribute. My second visit to his studio space gave a deeper insight into his practice and I found that comfortability and contribution were at the base of his creativity.

When you arrive at his space you are greeted by African sculptures of the Yoruba Orisha Exú that sit as guardians outside the studio, protecting the energy that lives inside. This immediately gave me the feeling of walking into a sacred space, as these “treasure guardians” were allowing us safe passage into the studio. You’re welcomed by a mountainous display of literature, reference material, and cultural artifacts that absorb three-quarters of the space, leaving the artist a fair amount of space to execute tasks. It always reminds me of my childhood when my mother would ask “How in the world can you find anything in all of this?”, and I’d respond “I know where everything I need is.” I’m certain it’s the same with J. Michael, as he navigates through it all to locate texts and objects to share for our visit.

On display (on the only wall absent his books) was a selection of seventeen midsize drawings, some completed while others sit in progress, offering different representations and poses of the female figure. I was intrigued by the origin of the collection as Walker explained that each began as a figure drawing exercise some twenty-five years ago. As he explains the work, there is a soft piano riff that plays on a small speaker in the studio, very timely background music for this presentation.

As he begins to move the series to another position on the wall to make room for the presentation of another work, he carefully unpins each drawing, treating each piece with special care. The work conveys a level of intimacy, a relationship of trust, and a deep dive into not just the physical, but the innate beauty of each subject and Walker handles them as so.

In one of his projects, a photo series titled “Bodies Mapping Time”, Walker lends that intimacy to the camera, injecting a mature gaze that presents the value of the spirit while using the body as a vehicle. “Bodies Mapping Time” presents dozens of women of all races at different stages of life, as they use photography for “self-empowerment, to overcome abuse and trauma, or to mark milestones in their lives”. The portraits remind me of the nude works of the renaissance with low lighting and high elegance, with Walker using natural everyday furniture, flowers, and objects to accent his subjects. “The reason that these portraits have power is that the women feel totally at ease,” Walker explains, “a comfort that allows them to be themselves and forget the fact that they’re not wearing clothes. My goal is to create an environment that makes the subject feel at ease so that their poses bring out their natural personalities.”

Walker’s figure sketches allowed me to envision Walker’s practice as more of a sculpture study, as he examines the different ways in which a body can be positioned with each pose evoking different emotions. He illustrated the process of sketching a human face that he taught to his class of 4th graders- before classes were halted by the COVID-19 pandemic. He starts by identifying the features that make up the human face and its attributes, simplifying the task, almost leading me to believe I could go home and replicate. Maybe I should sign up for the 4th-grade classes when the pandemic subsides? (Shoulder shrug).

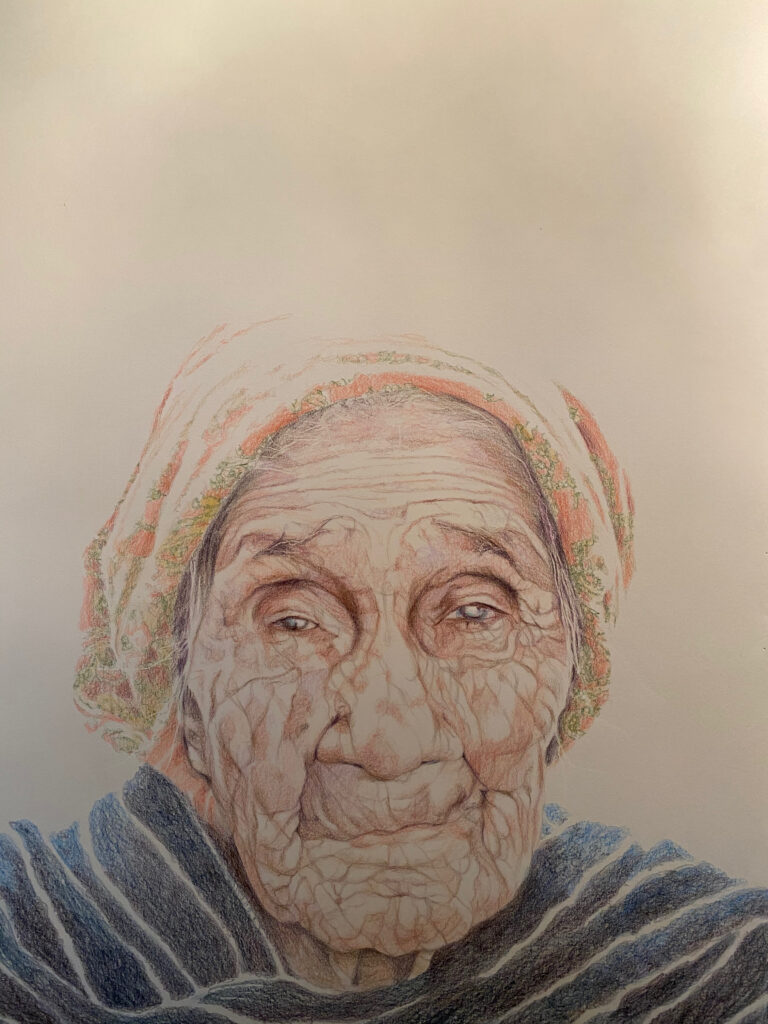

A question came to mind as Walker began to pin a recent portrait titled, “Retrato de Matianita,” to the display wall. “Is it always a subject in mind when artists create portraits or are there times when a person is created from a collection of faces, seen and unseen?” Walker thought back to his days of drawing as a youth seeing images and being able to personalize it, “make it mine”, in his words. The personalization in portraiture is the observer’s experience and interpretation, that still shot that we all have of a person’s face when someone says their name in remembrance.

After pinning the portrait to the wall and fudging with the speaker, Walker sits down to take a breather, but not before reaching over to a box of photos sitting on a stand near more sketch drawings. He shows photos of women from Oaxaca, Mexico on a recent trip. One photo that stands out immediately is of a young woman from the Folklorico dance troupe. She is dressed in a red patterned dress, with a matching headscarf with braided colorful fabric that dangled gracefully from it. The colors of the fabric complimented the bright blue of the rosary that she wore prominently around her neck.

She commands attention by just standing there, looking directly at the camera without striking a pose, surrounded by the natural foliage of the area. The photo is a real-world interpretation of Walker’s portraiture. He feels the power in women and uses his photography, drawing, and painting as a way to honor them. He continued telling stories of the people and his experiences of Mexico as a young man taking in the culture and learning the language, ultimately meeting his beautiful wife, Mimi. He spoke of this moment with great enthusiasm as he talked about his first time experiencing a new culture, turning twenty-two when he arrived. He spoke with a smile about the “drop-dead gorgeous teenage girl” that walked in while he was preparing illustrated texts with the nun he worked with. Prompting thoughts of “I have to stay.” (Laughs).

Walker spoke of embracing the culture, taking in the customs, and trying his best to keep up with the language. He wanted to communicate about the people, about his life, and how appreciative he was for being welcomed into such a loving community, rich with history. He began doing images, immediately finding the value in depicting actual people from the town. He felt it important that he show people in a way that exalted them, a different sentiment than he experienced growing up in the South where he encountered extreme racism toward the Black and Mexican populations. We spoke about how photography from the West (usually by white men), created a derogatory narrative about Latin American countries and the world in general.

He mentioned a photography book that he once came across in Chihuahua, Mexico – his adopted second home –, and how he became offended at how belittling the photos were about the culture. He waxed poetically about creating a project to counter that narrative. Dubbing it the “Invisible Handshake”, Walker looks to “tear down the North American photographer who has gone to Latin American countries and focuses on everything that evokes danger, poverty, and folks without hope”. This immediately made me think of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and his work with the male gaze as he looked at the bodies of black men, provoking discussions about race, power, and media – that still haunt our society today. J. Michael is hoping to use his photography to assist that narrative in correcting itself.

After a brief conversation on photography, we turn our attention to the “Retrato de Matianita” that’s displayed on the exhibit wall. These portraits, whether drawn or painted, are considered “Tributes” and are dedicated to the local elderly people in the municipality of Bocoyna, his wife’s homeland. Just like the elderly in our society, the show was hidden inside of the brutalist architecture of Consulate General de Mexico and now in his studio.

Hidden inside of the eyes of the subjects are decades of knowledge, experience, love, pain, and humanity. The focus is solely on the subject, not the artist as he abandons the traditional use of a background in his portraits to direct the viewers’ attention to the entirety of his subject. Walker made the choice not to include anything beyond the faces and a small fraction of clothing only to give a sense of where they’re from. By doing this, he hopes to relate the universality of his subjects. His thoughts are accelerated as he tells a story of a previous visitor comparing the likeness of the portrait to that of his Polish grandmother.

Expressions of gratitude, gratefulness, recovery, and deliverance draw you directly to the eyes of the work. Positioned low on the paper relates the size of the elderly woman with the blank space above as a reminder of where your eyes should be. This creates an intimacy with a stranger, a conversation with not the work but the eyes of a grandmother, the matriarch. He wants the viewer to feel like “they couldn’t escape the encounter with the person, just face to face.”

His use of the whitespace interprets the closeness of the subject to the earth. The use of this negative space works in unison with the pencil lines carved into the thick paper creating uncanny wrinkles, facial hair, and other detailed elements, revealing a level of life as if the likenesses were stamped directly from their person onto the paper. The colors, earth-toned with a graceful blue wrap lending elegance to the subject while simultaneously acting as a stabilizer, as you follow the carefully drawn patterns of the skin not missing a single feature.

Walker works until he feels that his subject is fully present, and then he stops. “If I keep working, then the portrait becomes more about me.” He feels the deepest responsibility to get it right with his wife as his first critic. She also has a personal connection to the work as she was the photographer who provided the referenced images in the series. He speaks with so much love and reverence about his subjects, trying to evoke the beauty and the spiritual essence of the person being memorialized.

He believes it is his gift to create loving, stellar portraits of people who have gone unheralded in life and would possibly never have had their portraits painted had he not done so. The elderly never like to be seen as weak, needing assistance, and/or a burden on society and Walker seizes the opportunity to make the ordinary, royal. He also thinks back to the photography when speaking about the people in the community saying, “I could never use the face of any of these people to say anything that would come across as disrespectful, who the hell am I?”. The portraits also act as a way for the family and community to steal back a moment of the loved ones who are no longer here, revisiting happy feelings, emotions, and memories.

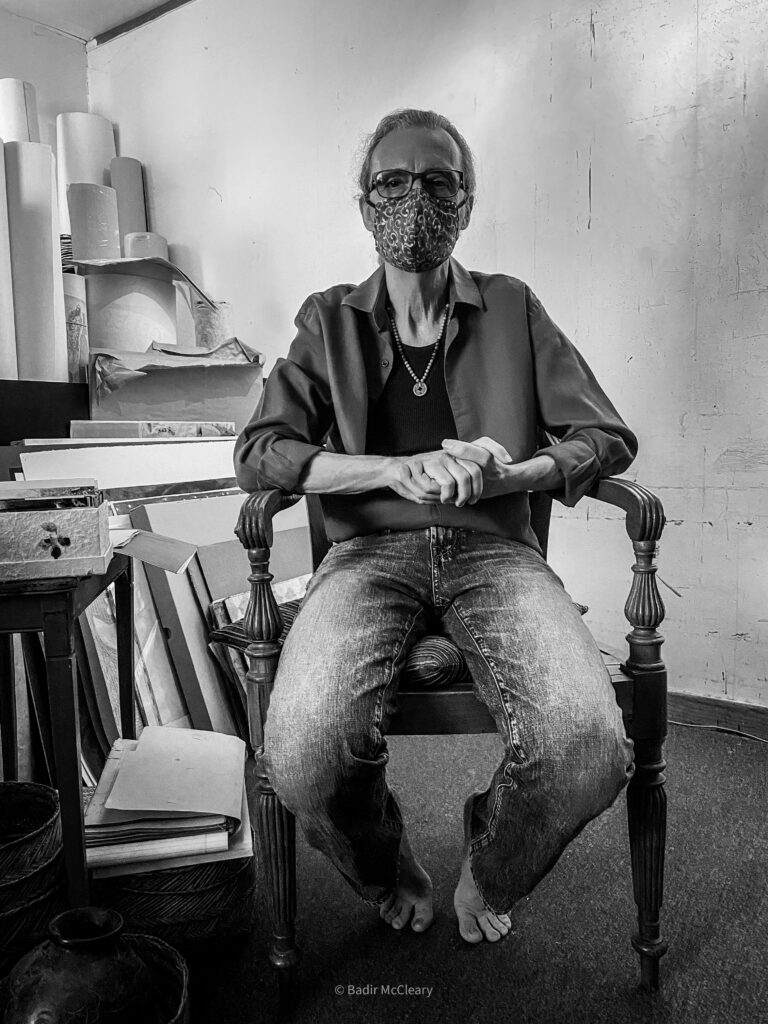

Just as he’d done earlier in the visit, Walker has a seat in his chair and begins to go through another box of random photos, much larger than the one that contained the image of the Oaxacan woman. Before he started to explain what was in the box, I stopped him for a photo in the seat just to capture the moment. The resulting image ironically took on the traits of the Oaxacan woman with the commanding stare (aided by the social distancing mask) as well as the negative space above the head as we saw in the tribute series. A bit of the artist’s repertoire comes full circle, this time with himself as the subject.

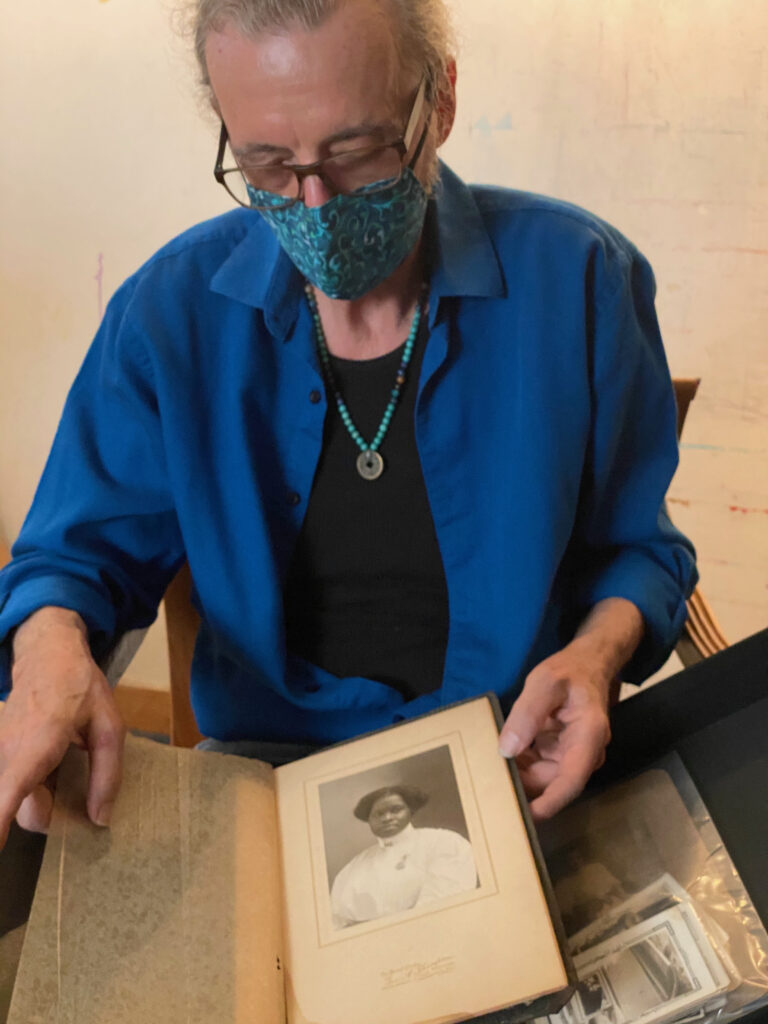

As he started to open the archival box, I noticed there are groups of photographs packed neatly with glassine sheets, carefully preserving its contents. Before thoroughly explaining what they were, Walker spoke of his 2000-2008 project titled “All the Saints of the City of the Angels”, an epic painting and text exploration of the multicultural heritage of Los Angeles via its 100+ streets named for saints. He prepared me for some of the images he found during his research, as many contained racist imagery or language that misrepresented the true nature of the people photographed. He spoke painfully about finding an early 20th-century postcard depicting a black woman breastfeeding her child, accompanied by the text “Free Lunch”, and we both gasped at the humiliation placed upon a natural maternal image.

It again brought us to the earlier conversation of misrepresentation through the photography of the West where in many cases, these photographers would make friends with and pay almost nothing to these poor children and/or their families for the impromptu shoot. Not knowing that the image could potentially be manipulated in meaning to a point where it would outrage those who participate. The images were not all negative though; Walker has collected images where the people of color depicted maintain agency, showing joy, success, and pride, showing the uplifting side of the growing city and the people that inhabit it. There was an image of a black woman preserved inside of a photo studio folder, seemingly in her mid-thirties, posing for her portrait of what seems like a graduation picture or maybe a professional career photo. We spoke about what the possibilities could be for these people and assumed where they could be today and how an image may represent a moment in time, it is never the final moment.

As I start to wrap up my time with J. Michael, I watch how he calmly and carefully places all the materials he displayed back into their rightful spaces in the studio not to disturb the energy inside the space. There is a high level of respect that he holds for the objects he collects. He felt he was culturally and spiritually reborn in Mexico and he hopes that experience is transplanted into each artwork he creates. As I walk out of the studio sanctuary, a familiar “Ashe Brother B!’” carries me out. I wave goodbye to the Orishas guarding the doorway and thank J. Michael. That feeling I described earlier heading to the studio was the same feeling Walker described when he arrived in Mexico for the first time. A sense of welcome, a familial hug.